David Cavagnaro in his forewords to my Sutter Buttes books wrote: “A naturalist, I think, is first a person of the earth, a shaman really, one who feels as well as sees, one who simply knows with greater depth and breadth than intellect alone can muster. Second, a naturalist is an interpreter, one who can translate the complex language of nature into the vocabulary of the common man, who can reach out to us from the heart of the natural world and lead us in.”

We can interpret with the language of science, but we can also appeal to the emotions through the language of art. Together, they are the tools of a naturalist, the means by which we draw connections.

If you check out the various pages of my website, http://www.geolobo.com/, you will see the balance of art & science that are my interpretive tools. My writing, photography, and trip-leading incorporate all these tools, and my paintings and other illustrations visually reach to a place in the heart that words alone may not penetrate.

Here are a few examples of paintings that suggest some of this kind of connection, but please go to my Interpreting Nature page for much more, and you can see art available for purchase at my Artists for Conservation site. My Artist Statement follows:

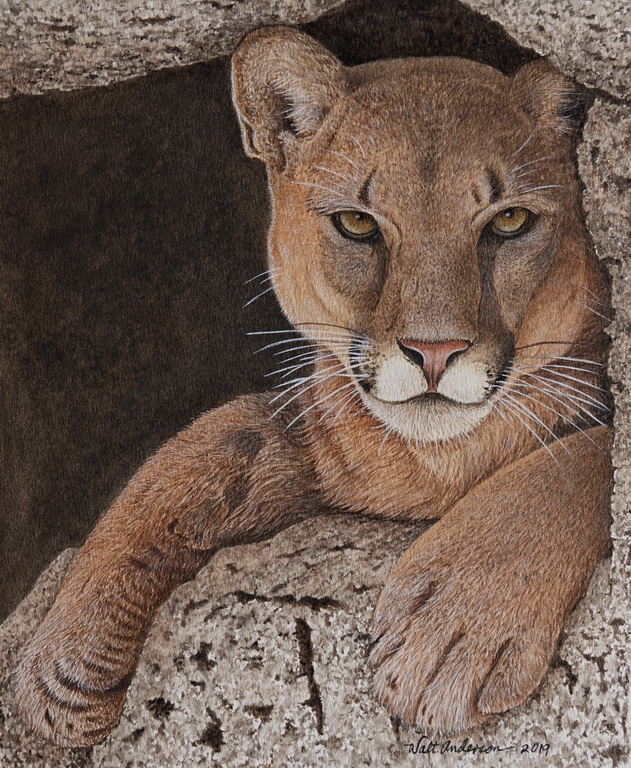

Kopje Cat

Mountain Lion, watercolor

Artist Statement

Evolution is the ultimate designer, and each organism reflects a winnowing creative process. Good design is beautiful, whether the product is as elegant as a gazelle or as comical (to our biased eyes) as a squat toad.

My goal as an artist is to interpret an organism with love, respect, and fidelity to essence. I love the delicacy of watercolor, which, though typically unforgiving as a medium, allows me to depict the softness of feather and the hardness of beak and claw equally well. I am now experimenting with other media, as the artistic process is enriched by media diversity the way a forest or grassland is enhanced through biotic diversity.

We often don’t see nature clearly; we may apply a name and then cease to observe closely, depriving ourselves and our subject of earned intimacy. I want you, the viewer of my paintings, to look more closely, to discover something that would not be apparent if you met an organism in the wild. If we can see clearly, we are blessed with priceless discoveries. Our human world is filled with distractions, many of them not good for our psyche. But marvel at the beauty of an animal well portrayed, and you can for a moment escape the confusion of modern society and connect with something much bigger and grander.

Walt Anderson